Intersectionality

A quick breakdown of dominant culture, intersectionality, and positionality.

Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw is known for coining the term intersectionality and if you’re in the realm of social work or anywhere near it, you hear this term quite a bit. However, when it comes to applying Intersectionality Theory - whether in mental health or in politics - there’s much left to be desired.

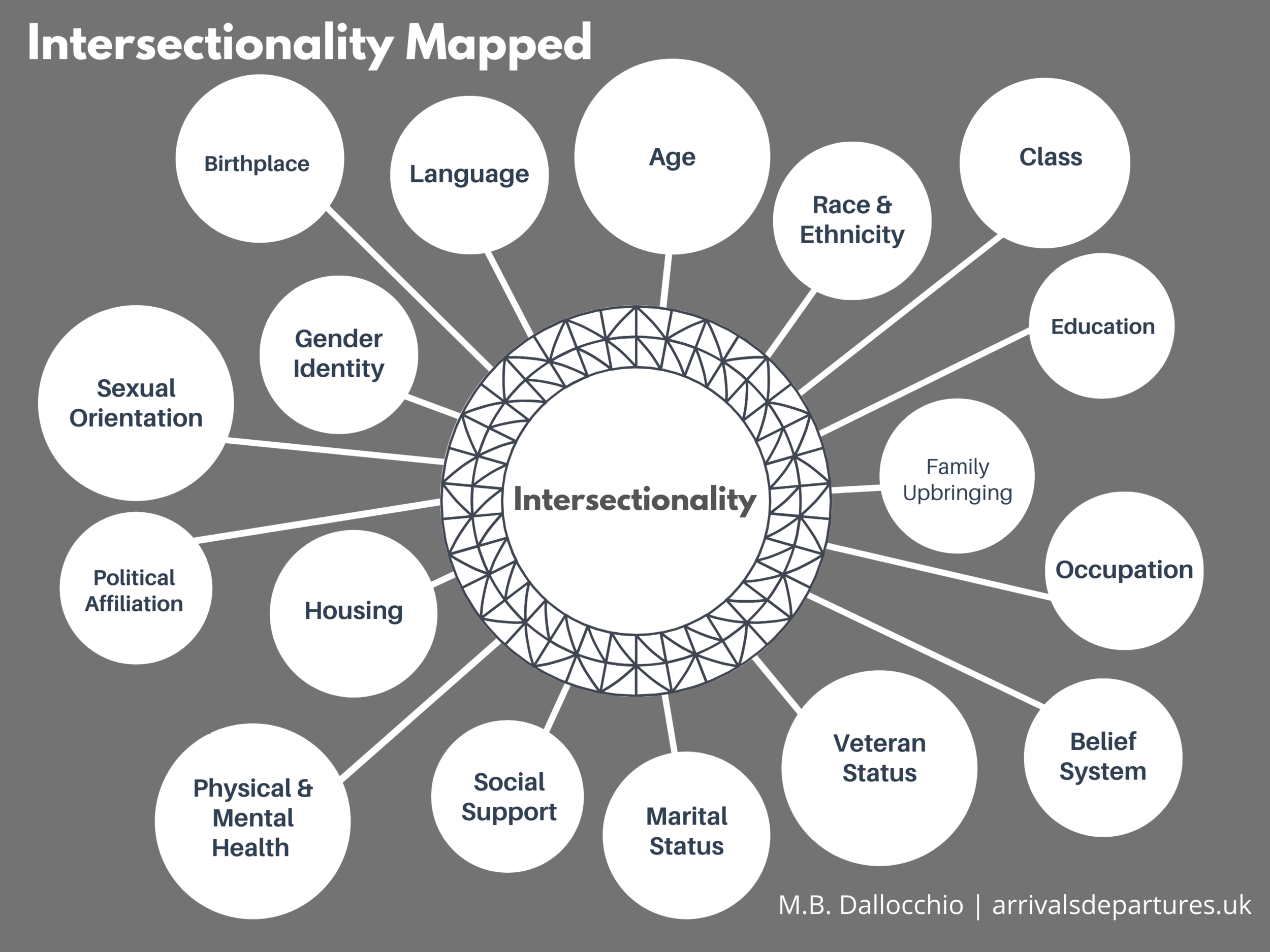

While studying social work at USC, intersectionality and positionality were discussed extensively - not only for our field of work, but something to be mindful of in every aspect of our lives. Being a visual learner, I felt compelled to create the infographics below.

Intersectionality Map

Because we’re not single issue beings, intersectionality highlights how intersecting identities we all possess affect the way we perceive the world and how we interact in it.

Who we are is so much more than a set of identity labels. If we’re to delve into interpersonal or systemic problem-solving, we have to take an honest inventory of our own positions within these systems as well as where others stand.

Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality is not exactly focused on superficial questions of identity or identity politics. Rather, intersectionality theory intends to provoke one to view people as complex individuals existing in a variety of systems.

Intersectionality starts with intersecting individual identities, but it leads directly to deeper, structural, and systemic questions about discrimination and inequality. This brings us to the mezzo/macro lens of positionality.

Positionality

Positionality implies that variations in one’s social position affect identity formation and access to power in society. It suggests that all intersecting aspects of our identity are influenced by socially-constructed positions and where we exist in those systems from a broader, macro perspective.

From a social work lens, positionality can be defined as Marisa Elena Duarte describes in Network Sovereignty: Building the Internet Across Indian Country. To paraphrase, positionality requires researchers and clinicians “to identify their own degrees of privilege through factors of race, class, educational attainment, income, ability, gender, and citizenship, among others” for the purpose of analyzing and engaging from one’s own social position “in an unjust world.”

Through both intersectionality and positionality, we can take another honest inventory of existing complex power dynamics - and what we may or may not be doing to perpetuate oppressive systems. When micro (intersectionality) and macro (positionality) perspectives are left unexamined and neglected, interweaving systems and injustice ensue and succeed. Overall, injustice and oppressive systems do not exist in silos, but collectively with organization and often a lot of financial and social capital.

Dominant Culture

When it comes to dominant culture, which is important to define along with other aspects of intersectionality and positionality, it can be defined as a group whose members are in the majority and/or who wield more power than other groups.

In the United States, the dominant culture is that of a cisgender, white, middle-class, Christian male of Anglo-Saxon descent in addition to the main identifiers listed below.

Dominant culture is one whose beliefs, language, and ways of behaving are imposed on a subordinate culture or cultures through economic, social, and political power. Institutionally, it is achieved through a variety of systems of power involving legal and political suppression.

Dominant culture, of course, perpetuates other sets of values and patterns of behavior accompanied by monopolizing media and other communication methods. It exercises gatekeeping in social and financial capital - which are key to maintaining those systems.

It exists and is upheld to marginalize and minimize power and agency of those who don't fit the intersecting aspects of dominant culture. There’s a LOT to unpack in terms of white supremacist patriarchy, but we’ll stick to keeping this as simple as possible for now.

On the surface, intersectionality and positionality deactivate easy-to-use stereotypes and demand actual effort in understanding individual experiences all the way to macro systems that affect us all in different ways. Dominant culture, at least how it exists in the United States as of late, suggests how enduring systems of oppression and injustice thrive in silence, fear, and control.

In order to enact long-term change, we need to be ready to have difficult and uncomfortable conversations with others as well as having the intestinal fortitude to be honest through our own introspection.

In the end, intersectionality and positionality aren’t about catering to the superficiality of identity politics or looking at humankind through rose-colored lenses - it’s about being real with who we are and the world in which we all live. If we fail to take stock of all aspects of ourselves and the systems we exist in, we also fail to make meaningful, impactful change regardless of where we stand.