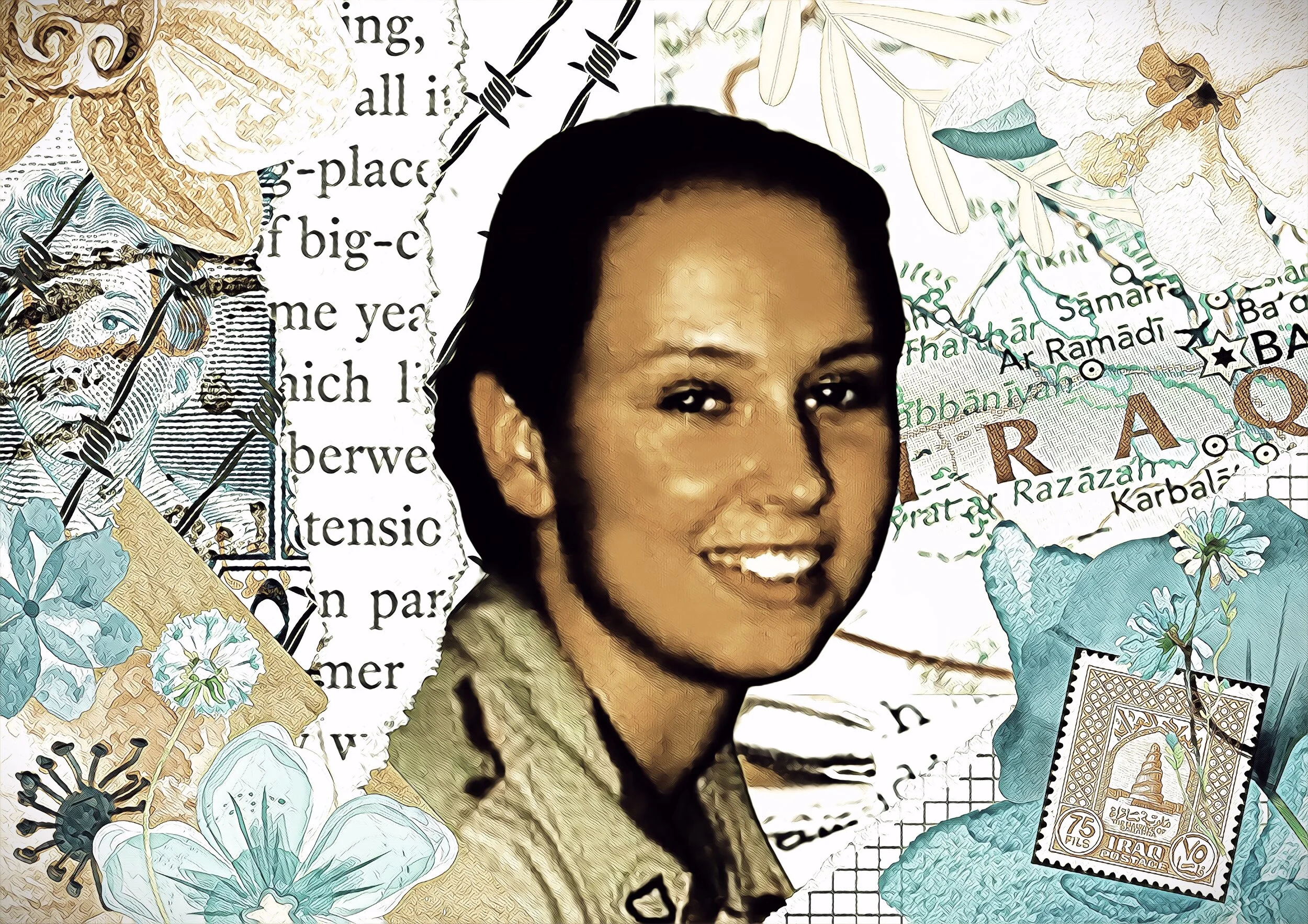

The Ballad of Liz Harrington

It was around 12:38pm on a Saturday when I learned about Liz’s death. Alex came to tell me in the living room as I was shuffling material in between multiple projects, and my heart sunk to the bottom of the sea. I decided to go for a run along the river. To clear my head, my senses, to push through the denial.

Like we ran on Team Lioness along the Euphrates River that cut through the Al Anbar Province Capital of Iraq during the war from 2004-2005, I found a momentary comfort in returning to the life we once knew even if I was now running alone along the Thames in London.

Along the Euphrates River in Ramadi, Iraq (2005)

Liz and I met in our first few weeks in Ramadi, Iraq. She was a Private First Class, fresh out of AIT and into Iraq working at 2nd Infantry Division's 2nd Brigade Combat Team Headquarters. As few women (40 out of 4,000 troops on FOB Ar Ramadi) on post, she had introduced Team Lioness to a fellow Soldier and I, which we soon started with her.

Team Lioness was the first female team that was attached to Marine infantry units to perform checkpoint operations, house raids, and personnel searches on Iraqi women and children for weapons and explosives.

Liz was an exceptional Soldier. She went above and beyond in anything she was asked, never complained about having to anything strenuous but had issues in dealing toxic leadership in the Brigade office. She often joked that she would rather deal with terrorists outside the wire than the terrorists with NCO rank in her office. Considering my own issues with my corrupt, white supremacist command in Baghdad, I could certainly relate with preferring getting shot at in Ramadi than dealing with imperialists in the Emerald City.

North Bridge, Euphrates River, Ramadi, Iraq (2005) where we often worked on Team Lioness among other locations in the Al Anbar Province capital.

On nights where we weren’t outside the wire, she would come over to the clinic where I worked and we would watch movies on a projector as other Marines in the compound would join in, share snacks, and make absurd comments on whatever we watched. It was like Mystery Science Theater 3000, but in uniform and in the middle of a desert.

During some of her visits to our compound, it became apparent that her unsupportive and often abusive leadership structure was affecting her. Liz’s story also was a familiar one. A troubled home life, a desire to escape, and hopefully be successful somewhere else, even if the Army could potentially take your life. Many of us who ran away from volatile or otherwise unstable home lives found solace even amid combat miles away from where we came of age. Home for many Soldiers, like Liz, had eluded us.

Lioness days with 2ID and 2/5 Marines (2005)

I offered Liz an extra cot in our room – just shared between another woman Soldier and I – that was hers anytime she needed to get away on those bad days. Sometimes people don’t understand how terrible it is not only to work with toxic people but having to live, eat, and sleep next to them as well is a completely different circle of hell.

After making it back to the United States, we had kept touch on and off. An email here or there to catch up, and later Facebook. In 2013, we held a Lioness film screening in Las Vegas where a few of us shared our experiences with attendees.

Later in the evening, Liz had shared with me her struggles in the homecoming process, and thanked me for writing about Iraq in Quixote in Ramadi and what women Veterans go through. I thanked her for also helping me keep it together, for being not only a battlebuddy, but a sister Lioness. If it weren’t for Soldiers like her being a light in the darkness, I don’t know how I would’ve pulled through my own dark night of the soul in Iraq.

“You know I’m Bi, right?” she asked.

“Yeah, I knew. Me, too,” I laughed.

“Yeah, I knew you were, too,” she laughed in confirmation.

Considering Don’t Ask Don’t Tell was still in effect while we were in the Army, many of us were not exactly jumping at the chance to tell anyone about our sexuality due to the risk of someone using it as ammunition against us. After the repeal in 2011, and we had already exited the military, we felt safe years later sharing what we already knew.

As the years went by, and conversations went on about homecoming woes, dealing with PTSD and Depression, we commiserated on our experiences with dealing with the VA Healthcare system. Tying to get benefits after having our combat service scoffed at or denied, facing microaggressions by bigoted Veterans, and blatant marginalization for Veterans like us made our homecoming an odyssey.

Even though in 2013, then-Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta rescinded the ban on women serving in ground combat units, our experience engaging in direct combat operations in 2004-2005 was completely ignored and treated as a fabrication by people who were supposed to be providing our care. Unfortunately, these service-connected injuries and trauma that compounded our experiences also extended to other areas of life.

“How can people tell you they love you and then vote for someone who obviously wants to hurt you?” Liz said in a conversation about seeing former comrades and loved ones jump onto the Trump bandwagon and share homophobic, misogynist, and other bigoted memes.

“This is why I want to leave,” I replied, empathizing with her disappointment. As she was searching for somewhere to feel safe and accepted, I offered her a spare bedroom in our home in Las Vegas until she got on her feet.

“I don’t want to be a burden,” Liz would say.

“You’re never a burden. You’re family,” I’d reply.

“Okay, Grandma B,” she’d laugh.

In Ramadi, she would call me Grandma B because I was always making sure she had something to eat, some extra snacks I got from a care package. Was she sleeping enough? Did she have time to call her family back in the US? It wasn’t that I thought she couldn’t take care of herself, it was that I saw a trait in her that I had: the reluctance to accept help.

As much as she claimed she didn’t want to be a burden, I would share with her that accepting help is what got me though a disaster of a homecoming. That it was okay to let people give you a helping hand up as no one is an island. When we moved to Los Angeles, she was moving from Florida to Nebraska and promised to come visit. She had talked about a road trip through national parks and then arriving in LA to hang out. Alex and I were thrilled.

Then communication stopped.

I would call and text to check in but no response. Months later she surfaced asking for money, sounding both frantic and paranoid. Even if we didn’t speak for months, we always knew we could circle back to one another like so many of my itinerant friends, and it seemed absolutely unfathomable that she wouldn’t be there one day.

“Tell me what’s going on, Liz,” I asked with genuine concern. I felt something terrible in my gut.

I asked her to get onto video chat where she looked like a completely different person. She wouldn’t make eye contact with me and seemed to be speed-walking through a trailer park in Omaha, Nebraska.

“I’m fine, everything is okay,” she said.

“Liz, tell me what’s going on so I can help you. Please,” I pleaded.

She said that she had to go and I followed up with local resources in Omaha, pleading for them to make contact with her. As a bi woman combat Veteran, she was denied VA benefits as well as any dignity pertaining to her service-connected conditions from combat in Iraq and toxic leadership.

Liz saw me fighting for VA benefits, and while it still is a soul-crushing battle for benefits decades later, I urged her to never give up trying. Fighting for benefits and help - and not being heard - is something none of us should have been subjected to, and when Liz needed those resources the most, they weren’t there.

She shared with me that she had been struggling, hinting at relapse from an addiction, and had been spiraling. Again, I offered help, to come out to LA before we leave for the UK, and that no matter what she was dealing with that we loved her.

“I will come visit. I just need to get my head right first,” she said.

She claimed she was seeing someone regarding her relapse, and knew it was time to accept help. She wanted the type of VA Healthcare that was supposed to help Veterans like her.

For Alex and I, she was the little sister we never had. We reiterated that we loved her and would be there whenever she needed us. However, months later, it was radio silence yet again. I had reached out to her cell, messaged her when we got to London, but no response. She had posted to Facebook a few times but had been quiet otherwise. Maybe I’m pushing too hard? Maybe she needs space, I thought.

On August 20, 2021, Liz took her own life.

Alex had come racing into the living room where I was working and said, “I think Liz might have passed away.”

I immediately went to the post on Facebook that was shared by her sister and reached out. Her sister immediately responded and I offered my condolences. Apparently, not too long after moving to Nebraska, Liz had fallen in with the wrong crowd. People who took advantage of her, took her money, and offered an escape from her pain when reprieve seemed to be so far out of her reach.

Having dealt with trauma from childhood, through combat in Iraq, and then a homecoming that told her she didn’t belong, that her service as a woman was denied by VA Healthcare personnel, it appeared that Liz lost all hope.

While VA claims to have resources, they had wildly failed when a woman combat Veteran needed it most. While VA did not pull the trigger, they sure did put the metaphorical CLP on her bolt carrier. This combination of systems failures, addiction, and general apathy for her pain paved a smooth and open road to her suicide.

As I sit through days and weeks of going through the stages of grief, denial slipped past me, anger got me writing and seething with rage at the multiple systems that failed her. I found myself bargaining for time to pause and rewind back to those precious moments we shared on earth while she was alive and to keep reminding her not to forget to call me when she’s in trouble. The depression of knowing life will exist without her and that there will always be a piece of my heart that feels her absence, and finally the acceptance that she is now gone.

I recall all the moments we spent watching films late at night when she would escape her compound and head to our clinic. 3am, watching sappy Hugh Grant movies in marathon-mode on some bootleg DVD a Turkish contractor gifted us. There was a poem being read at one point in Four Weddings and a Funeral.

“I like that poem,” she said.

As I stare out over the Thames and let a sigh out whispering her name, I think back to that W.H. Auden poem she liked so much. The ballad of my dear Liz.

Funeral Blues

Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone,

Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone,

Silence the pianos and with muffled drum

Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come.

Let aeroplanes circle moaning overhead

Scribbling on the sky the message ‘He is Dead’.

Put crepe bows round the white necks of the public doves,

Let the traffic policemen wear black cotton gloves.

He was my North, my South, my East and West,

My working week and my Sunday rest,

My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song;

I thought that love would last forever: I was wrong.

The stars are not wanted now; put out every one,

Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun,

Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood;

For nothing now can ever come to any good.

To find out about her passing thousands of miles away? It might as well have been a million. Another universe where this would just be a dream and I’d wake up to hear her voice in a message, telling me she just needed some time to herself to get better, and that she was on her way to visit us. I told her that I would always be there, and it pains me that in all the obstacles she had faced since childhood and through combat, she felt so alone in her last moments that suicide appeared to be her only way out.

In processing my own grief, I wonder what life would have been like if Liz was treated with dignity as a bi woman, a combat Veteran, a person in the world who needed help in processing trauma. What if she had been taken seriously regarding her PTSD, Depression, and her battle with addiction? Would she still be here? I ask myself this everyday as I’m still fighting the VBA for benefits relating to combat-PTSD to this day and navigating discrimination in the process.

As I continue to look out over the Thames, I think of that poem while the sky opens up and weeps over London and carries our tears away through the river. Our big-hearted Lioness Liz who would state that she didn’t want to be a burden, who just needed to feel safe, accepted, and loved. The biggest burden of all is knowing she might’ve been alive today if the help she desperately needed was there for her to accept.

When in crisis, offering those who are struggling a hotline alone is not enough. We must all be willing to sit with those who are hurting, no matter how uncomfortable the silence may be, to let them know they are not alone and that they are unconditionally loved.

Liz Harrington’s funeral is to take place at Cape Canaveral National Cemetery in Mims, FL at 1100, October 22, 2021.

Be sure to reach out to your battlebuddies and check in. If you or a Veteran you know is in crisis, you can also reach out to the Veterans Crisis Line at 1-800-273-8255 or text 838255. However, I also ask you to do your best to be there for those who are struggling with their trauma.

If you're going to donate to Veterans organizations that assist Veterans like Liz, consider donating to Minority Veterans of America as in her lifetime, many VSOs didn't acknowledge her combat service nor her identity at all. To assist women combat Veterans, LGBTQ Veterans, ethnic minority Veterans, and all other Veterans who have been historically disenfranchised and marginalized, visit minorityveterans.org for more information.

We miss you Liz. Until we meet again.